Uncommon Fruits is a project born from the collaboration between the extended Robida collective (Topolò, Benečija) and Zavod Cepika (Kojsko, Goriška Brda) that investigates two different landscapes through the lens of fruit trees: one, Goriška Brda, characterised by an almost-monoculture of vine and the other, the one surrounding Topolò, by abandonment.

Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.

– Noam Chomsky

Photo: Gregor Božič

On humans inducing plant desire, according to St. Augustine: “In the case of trees, their nourishment and generation have some resemblances to sensation. Yet, though they and all corporeal things have causes which lie hidden in their nature, they do display their forms, which give shape to the visible structure of our world, for perception by our senses; and so it seems that, even though they themselves cannot know, they nonetheless wish to be known.”1

On plants inducing human desire, according to Michael Pollan: “Bees and humans alike have their criteria for selection: symmetry and sweetness in the case of the bee; heft and nutritional value in the case of the potato-eating human. The fact that one of us has evolved to become intermittently aware of its desires makes no difference whatsoever to the flower or the potato taking part in this arrangement. All those plants care about is what every being cares about on the most basic genetic level: making more copies of itself. Through trial and error these plant species have found that the best way to do that is to induce animals— bees or people, it hardly matters—to spread their genes. How? By playing on the animals’ desires, conscious and otherwise. The flowers and spuds that manage to do this most effectively are the ones that get to be fruitful and multiply. [...] That May afternoon, the garden suddenly appeared before me in a whole new light, the manifold delights it offered to the eye and nose and tongue no longer quite so innocent or passive. All these plants, which I’d always regarded as the objects of my desire, were also, I realized, subjects, acting on me, getting me to do things for them they couldn’t do for themselves.”2

1 St. Augustine, The City of God, 11.27.

2 Michael Pollan, The Botany of Desire: A Plant's-Eye View of the World (2001, Random House)

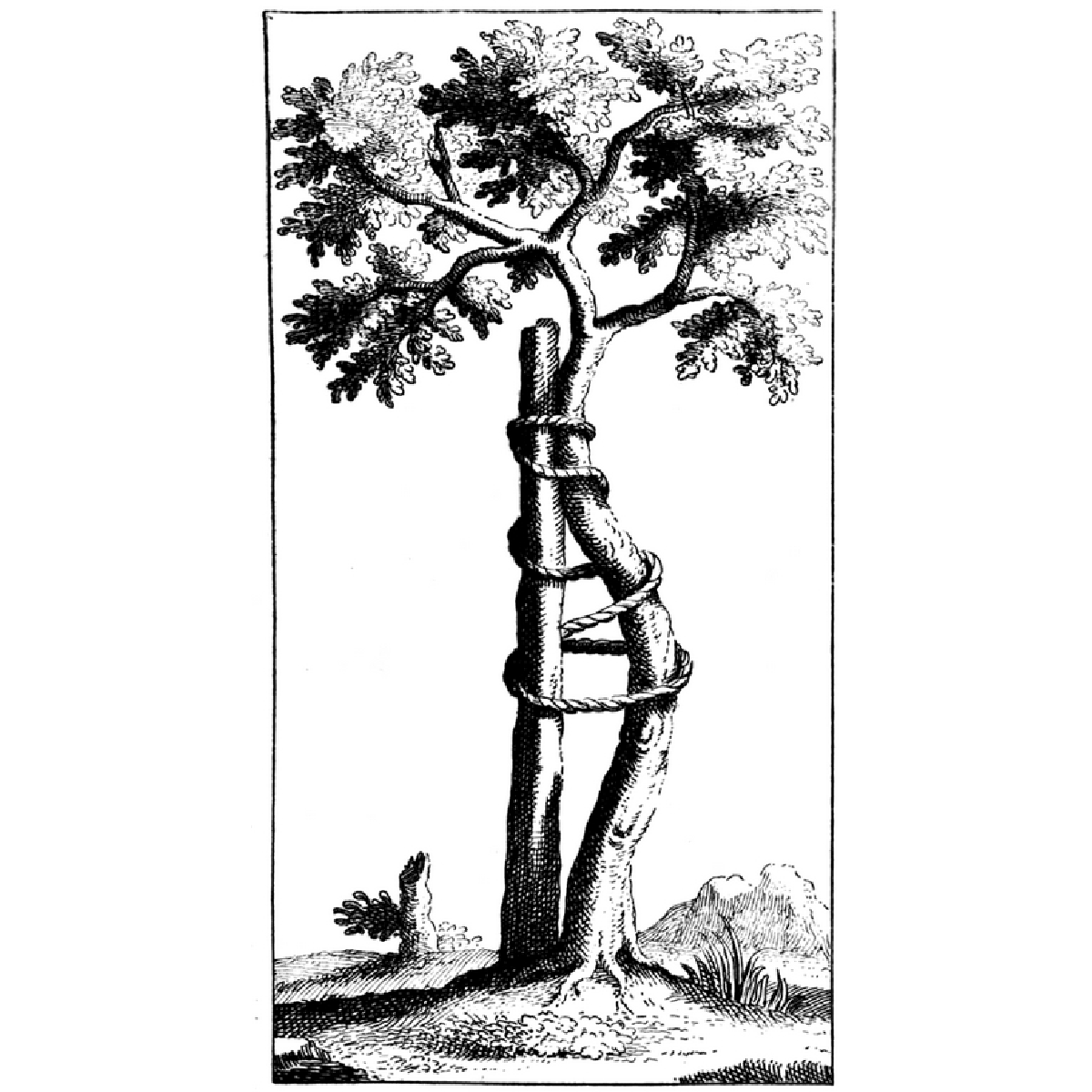

"Carpenter Shi went to Qi and, when he got to Crooked Shaft, he saw a serrate oak standing by the village shrine. It was broad enough to shelter several thousand oxen and measured a hundred spans around, towering above the hills. The lowest branches were eighty feet from the ground, and a dozen or so of them could have been made into boats. There were so many sightseers that the place looked like a fair, but the carpenter didn’t even glance around and went on his way without stopping. His apprentice stood staring for a long time and then ran after Carpenter Shi and said, “Since I first took up my ax and followed you, Master, I have never seen timber as beautiful as this. But you don’t even bother to look, and go right on without stopping. Why is that?”

“Forget it—say no more!” said the carpenter. “It’s a worthless tree! Make boats out of it and they’d sink; make coffins and they’d rot in no time; make vessels and they’d break at once. Use it for doors and it would sweat sap like pine; use it for posts and the worms would eat them up. It’s not a timber tree—there’s nothing it can be used for. That’s how it got to be that old!"

After Carpenter Shi had returned home, the oak tree appeared to him in a dream and said, "What are you comparing me with? Are you comparing me with those useful trees? The cherry apple, the pear, the orange, the citron, the rest of those fructiferous trees and shrubs— as soon as their fruit is ripe, they are torn apart and subjected to abuse. Their big limbs are broken off, their little limbs are yanked around. Their utility makes life miserable for them, and so they don’t get to finish out the years Heaven gave them but are cut off in mid-journey. They bring it on themselves—the pulling and tearing of the common mob. And it’s the same way with all other things.

As for me, I’ve been trying a long time to be of no use, and though I almost died, I’ve finally got it. This is of great use to me. If I had been of some use, would I ever have grown this large? Moreover, you and I are both of us things. What’s the point of this—things condemning things? You, a worthless man about to die—how do you know I’m a worthless tree?""

Zhuangzi, The Complete Works of Zhuangzi (Columbia University Press, 2013), pp. 30–31.

“If Plato beseeched us to awaken to the radiance of Ideas from the apparent certainties of physical reality as though from a nightmare, Heidegger asks us to awaken from this very awakening, so that we could meet beings (whether human or not) for the first time on their own and our turf, in the sphere of existence. The apple that fell on Newton’s head did not interrupt his slumber but only deepened it. For all the buzz around the Enlightenment, we are still sound asleep; awakening would then mean accepting beings, including the apple and the apple tree, just as they are.”

Michael Marder, The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium (2014, Columbia University Press)