Learning from Kozolci

Editor’s note

The words in this text have flowered from the cross-pollination between Uncommon Fruits and Folly, with the English print version available at https://follyarch.info/. Though the architecture of the kozolec is not tied to fruit trees, it belongs to the same world of cultivation. We chose to publish “Learning from Kozolci” on Uncommon Fruits because, in its own way, the kozolec is an uncommon fruit of the land.

- - - -

Although Renzo Rucli has not written his autobiography yet, he already has a title for it: Dal Medioevo alla Modernità (From the Dark Ages to Modernity). Born into a peasant family in a small village in the mountains between Italy and (at the time) Yugoslavia, Renzo managed to put himself through architectural education despite all obstacles. And yet, throughout his professional life in the fine arts of building, he has always cultivated a profound interest in the rural context he came from; this led to various studies and publications on the vernacular architecture of his village and region.

Of particular interest to Renzo was the kozolec (or kozolci, in plural). From childhood, this agrarian typology occupied an important place in his life, as its built form suited the foremost needs of his youth by functioning both as a playground and as a hideout. Later on, ripened by his initiation in the discipline of architecture, the solemn presence of the kozolci stone pillars in the mountainscape tormented him like the sphinx’s riddle: ‘decipher me or I'll devour you.’ ‘I found myself’, Renzo told me, ‘with this thing that gave me no explanation whatsoever’. (1)

Rucli’s research regarding the kozolec began while writing a book dedicated to the architectural and ethnographic history of his home village, Topolò/Topolove. Initially, this led him to the writings of Slovene Geographer Anton Melik, dating from the 1930s, and later to architectural publications from the 1970s by Marjan Mušič, Jože Brumen and Marko Mušič (2) – most likely animated by the spirit of Bernard Rudofsky. Yet none of these references adequately addressed the particularities of the kozolci Renzo saw around him. Living within walking distance of his case studies, he was able to conduct his field research, documenting the remaining examples. His findings culminated in a bilingual edition published in 1998, titled Kozolec: monumento dell’architettura rurale/spomenik ljudske architekture.

Despite having been abandoned for decades, the agrarian relics that captivated Renzo’s imagination can still be found in good condition – if one knows where to look. And so, in the early spring of 2025, I went into the forest with Renzo Rucli to find a ruin: an overgrown kozolec he had studied a quarter of a century earlier.

We follow an overgrown path for a while, then suddenly take a sharp turn and start climbing a steep hillside that bears no apparent trail. ‘The old access was somewhere here’. As we approach the site, Renzo explains to me that the kozolec itself is already an exception to the ordinary typology – and that somewhere between where we are standing and central Slovenia, the exception to the exception was cultivated.

In an elementary sense, the kozolec is a hayrack: an assembly of wooden rods used for drying yields. ‘This structure can be found everywhere, from Scandinavia to Russia, but around the Slovene Alpine arc, the rudimentary rack became a building.’ He continues:

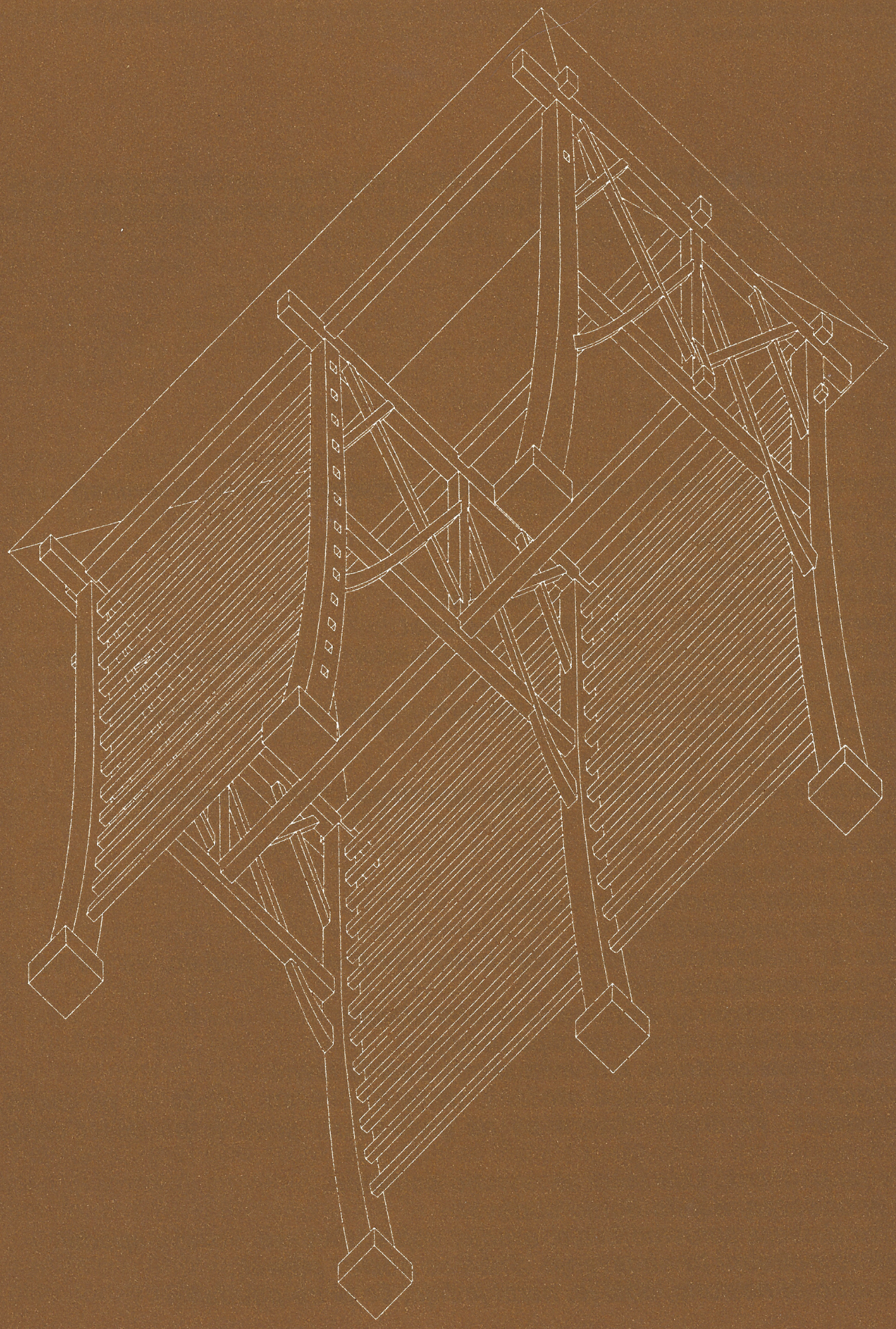

RR: This is the peculiar thing. Through functional adaptations – even logical – little by little, from a simple linear structure, another one was added. First, a roof was put on each line, then a single roof was built between two parallel lines. Then someone probably made the leap in scale. Up to that point, it was still a piece of equipment; it was not yet a building.

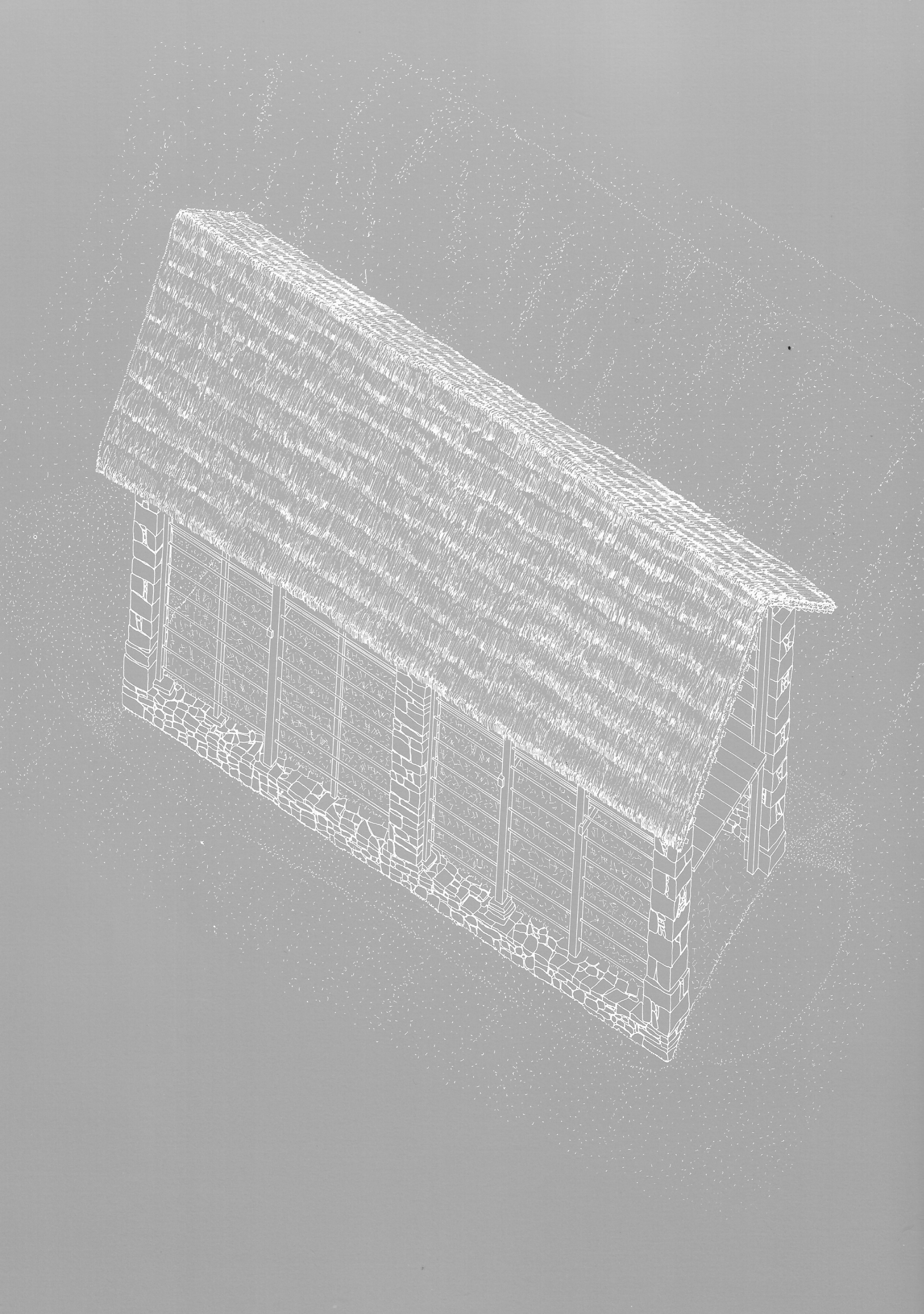

Hayracks are found anywhere that cultivated crops need to be dried. In its simplest form, a pile structured by a central pole suffices. In areas of high precipitation, however, these structures often require a roof to protect them from rain. Hence, the presence of the linear kozolec all over Europe, as Renzo points out. The intriguing thing is that, for some reason, in the area under Slovenian influence, this impermanent structure became a building in its own right.

RR: From a conceptual point of view, the issue is this: the kozolec – and I think only a few buildings in history follow this path – was not born as a construction, but evolved from a process in stages. Usually, a building is built because you want to build the building. There is no transition from equipment to building. In this case – and that is what’s interesting – there is this very slow passage of adding parts until you get a building.

AFL: What do you mean by ‘transition from equipment to building’?

RR: The original kozolci, all made of wood, had the character of an instrument. An instrument, because there were many cases where a farmer would sell the kozolec, dismantle it and take it somewhere else. You could assemble and disassemble it, like any other piece of field equipment.

AFL: I guess this would be harder here, with the stone pillars.

RR: Exactly. And so I refined the problem that arose, as you said, because here the kozolci have not retained the wooden pillars. And surely this is not a building invented by someone from Topolò – they probably saw it somewhere else in central Slovenia and decided to copy it here. Wooden pillars are always problematic at the point where they meet the ground – they rot over time. You’d have to change them every fifty or a hundred years. So, someone decided to replace wood with stone.

Although the change in materials restricted mobility across space, the use of masonry in the pillars brought advantages in terms of durability over time; as Renzo points out, the tectonics of the Slovenian kozolec underwent two significant metamorphoses that characterise its unique identity. First, it became formalised as a structure with the addition of a roof; and second, it evolved from a temporary apparatus into a perennial building with build pillars. The clearest examples of this typology as a true edifice can be found around Škofja Loka, heading towards the Soča Valley via Idria and Tolmin, in Slovenia, and continuing across the border into Italy.

RR: Now the question is: why does this transformation take place in this area? Of course, we must consider the fact that there's the availability of stone here that's easier to work with, but I believe there’s a cultural factor at play. We can put it this way: the master builders of the late Gothic churches lived and worked in these areas. They built many small Gothic votive chapels which are still visible today – in Benečija there are 25. We're around the year 1450, on the other side of Italy, the Renaissance had already begun in Florence. And yet, here there was still this school of masons – that is, architects. The territory had been inhabited by people capable of building the Gothic church, with its ribs, vaults, and so on. Most likely, someone with this knowledge influenced the construction of the kozolec. You can’t document this – it’s impossible – but we witness this coincidence: the presence of the skilled builders of the Gothic churches and the consistency of stone masonry in the kozolci.

AFL: Curiously you bring up the construction of sacred spaces because the kozolci do carry a feeling of cosmic harmony – a spiritual connection with the land. In any case, the building techniques used in most masonry examples, which expose their raw structure, seem to support your theory of Gothic influence.

RR: Yes, there was indeed a strong Gothic influence. In the Slavic world, there are many places where the Gothic found its strongest expressions – the best architects were in Prague, no? For me, St. Vitus Cathedral is much more powerful than Notre Dame. Prague, Moravia, and Austria were all zones of intense cultural exchange and architecture emerged from these processes of sharing knowledge.

AFL: Five centuries later, the kozolci still stand as witnesses to the empirical encounter between the Alpine, Slavic, and Mediterranean worlds. (3) I want to return to your biography and lived experience, precisely around the relationship between the Italian and the Slovenian culture, which was part of Yugoslavia when you were growing up during the Cold War. Was there any stigma toward the kozolec during that period?

RR: In my opinion, the battle here was over language. You couldn’t speak Slovenian in school. Language carries a strong identity – it’s both very personal and collective. When I went to school, I barely knew Italian. And there, the teachers taught only in Italian, so you already had difficulty learning, passing exams, and so on. From the Unification of Italy onward, there was a strong push to Italianise Italy, even in Sicily. But here, the struggle was harder because the Slovenian language had nothing to do with Latin. So we were seen as a foreign body that had to be assimilated. That was the concept. But about things like this – the kozolec, fruits of a culture – people didn’t know. No one knew anything about these things. An Italian doesn’t know anything about them. And it’s curious, because the kozolec is also part of Slovenian identity. It's a mark, something that tells you about a way of life. For example, I was very impressed when I once went to Brunico, in Trentino, and saw the kozolec in the whole valley, from Klagenfurt almost up to the pass and down into South Tyrol. There, the German assimilation happened much earlier than here. Farmers still take care of their kozolci, but they don’t know that they’re looking after something that came from a now-vanished identity, even if it had a historical and cultural continuity.

AFL: In fact, you do refer to the kozolec in your book as ‘monuments of a lost peasant civilisation’. As a material expression of life, what does the kozolec say about dwelling in this place?

RR: To live in the peasant world means to experience a hard life, especially here. And that means its material expressions must find the most efficient solutions possible under those conditions. In this context, work, artefacts and territory form a symbiosis. I do not want to idealise it too much because the other side of the coin is backbreaking labour. But in my opinion, the kozolec is the only building which lends itself to the character of a monument. The barn isn’t fit for it, nor is the hunting lodge, because these types of buildings continued to be used over time. The kozolec, in contrast, has such a bare expression, it’s so fit to its function, that it is hard to think of something else to do with it: it can be a monument. A monument serves no purpose. Its function is simply to be present.

AFL: But you said that the Slovenian kozolec suffered two transformations already. Could we not imagine it undergoing another metamorphosis that might give it new uses?

RR: This entails larger problems. It is not only a matter of architecture, but a question of the transformations of society and how we live. Some people today try to find new uses for this structure, with varying degrees of success. But the fact is that these buildings are beautiful, even beyond the question of culture, construction, etc. The kozolec has a strong character, and it is in harmony with the place. Perhaps this is the point from which we could work.

The social transformations Renzo refers to stem from the transition from an agrarian way of life to urbanised living. As people moved elsewhere and agricultural technologies became mechanised, the kozolec in these mountains became an obsolete infrastructure. The sense of abandonment felt today is not only due to physical decay but also the loss of seasonal rites, resulting in a homogenous facade throughout the year. As Renzo Rucli recalls in his book, there was a time when the act of drying yields represented a periodic transformation in the kozolci character: ‘Through these loading/unloading operations, the building changes ‘dress’ and the external facades take on the tactile and chromatic variety of the products being dried, the yellow of wheat, the grey of hay, etc’. (4) A generation later, Vida Rucli cultivates the metaphor of a building which marks the cyclical passage of time by referring to the kozolec as ‘a calendar in the shape of a house or a temple’. (5)

AFL: Returning to your experience as an architect, what has the kozolec taught you over the years?

RR: The kozolec taught me about the essentiality of form – how to derive structure from purpose, with the least possible waste. Here, you can see that the heights are proportioned according to use and economy, but these variations also become expressive. The upper part is more spacious than the lower, so up there you feel like you can breathe, and down here you feel more protected. But above all, the whole thing feels properly planted. Sometimes it seems to me that this building just sprouted from the ground, as if it had grown here naturally. I like this metaphor. I mean, a building is a landscape, isn’t it? I took this lesson to heart when I built my own house in Liessa. (6) When I look at it, I get the impression that it’s just right, quietly sitting there in the landscape. To answer your question: the modulation of sensations that a space can offer, together with the matter of context, which, in the end, is the fundamental problem of architecture – these are the things I learned from the kozolec.

Even as partial ruins, the kozolci stand as tangible evocations of the place and culture that cultivated them. Whatever the future may hold for the few examples still standing today in Benečija is uncertain. Though very little maintenance is necessary to keep these structures in good condition, the unfortunate reality is that there is a visible (and perhaps irreversible) decline in their material state over the past decades. Being structures seemingly disconnected from the values and concerns of the present, the kozolci are gradually falling out of use and care. In the absence of conditions for their support, these buildings risk disappearing from lived experience, surviving only in the disembodied pages of architectural publications. Yet, while the robustness of their stone pillars still sustains wooden poles above the ground, they remain as places for imagination and potential transformation. Either as a site of memory liberated from function, or as an analogy in situatedness to incorporate into practice, there is a lot to learn from the kozolci.

- - - -

Bibliography

Melik, Anton. Kozolec na Slovenskem. Razprave znanstvenega društva v ljubljani, 1931.

Michieli, Tommaso. Saponaro, Filippo. Falaschi, Elia. A casa dell'architetto. Gaspari, 2024.

Mušič, Marjan. Arhitektura slovenskega kozolca. The Architecture of the slovene ‘kozolec’ (hay-rack). Cankarjeva založba, 1970.

Rucli, Renzo. Kozolec, monumento dell’architettura rurale / spomenik ljudske arhitekture. Cooperativa Lipa, 1998.

Rucli, Vida. “Kozolci: architecture and the cyclicity of time.” in Ajda Pratika. Robida, 2022.