On Arborescent Culture

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari offer a potent criticism of trees, arborescent structures and images of thought in their A Thousand Plateaus (1980), in which they write: “We're tired of trees. We should stop believing in trees, roots, and radicles. They've made us suffer too much. All of arborescent culture is founded on them, from biology to linguistics.” (1) Their disdain for trees is a clear critique of hierarchical structures of organization and the principles of Western culture in general: the tree is centralized, always growing from a unified origin—the rigid trunk—, which in its verticality strives towards the Platonic world of ideas and transcendence. Its roots, buried deeply in the earth in contrast to the branches reaching upwards, symbolize the European quest for the ‘foundation’ of thought, a central theme in Western philosophy, notably in the works of René Descartes and Immanuel Kant. The search for this foundation is mirrored in the roots of a tree: rigid, firm, solid, immovable, and ultimately paralyzing. Looking at a family tree, for instance, dictates one’s identity and place in the world, leaving little room for deviation. No need fighting it — that is who you are.

Deleuze and Guattari prefer the image of thought propagated by the rhizome. A rhizome is an expression of untamed multiplicity; it is non-centralized and non-hierarchical; it “may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines,” write Deleuze and Guattari. Furthermore: “The rhizome is an anti-genealogy.” (2) It promotes genetic drift and transduction, facilitating communication and translation between different species. It rejects mother tongues and generates new languages, severing ties with the past and its genealogy.

A rhizome is progressive, while a tree is conservative. A rhizome is good, tree — bad.

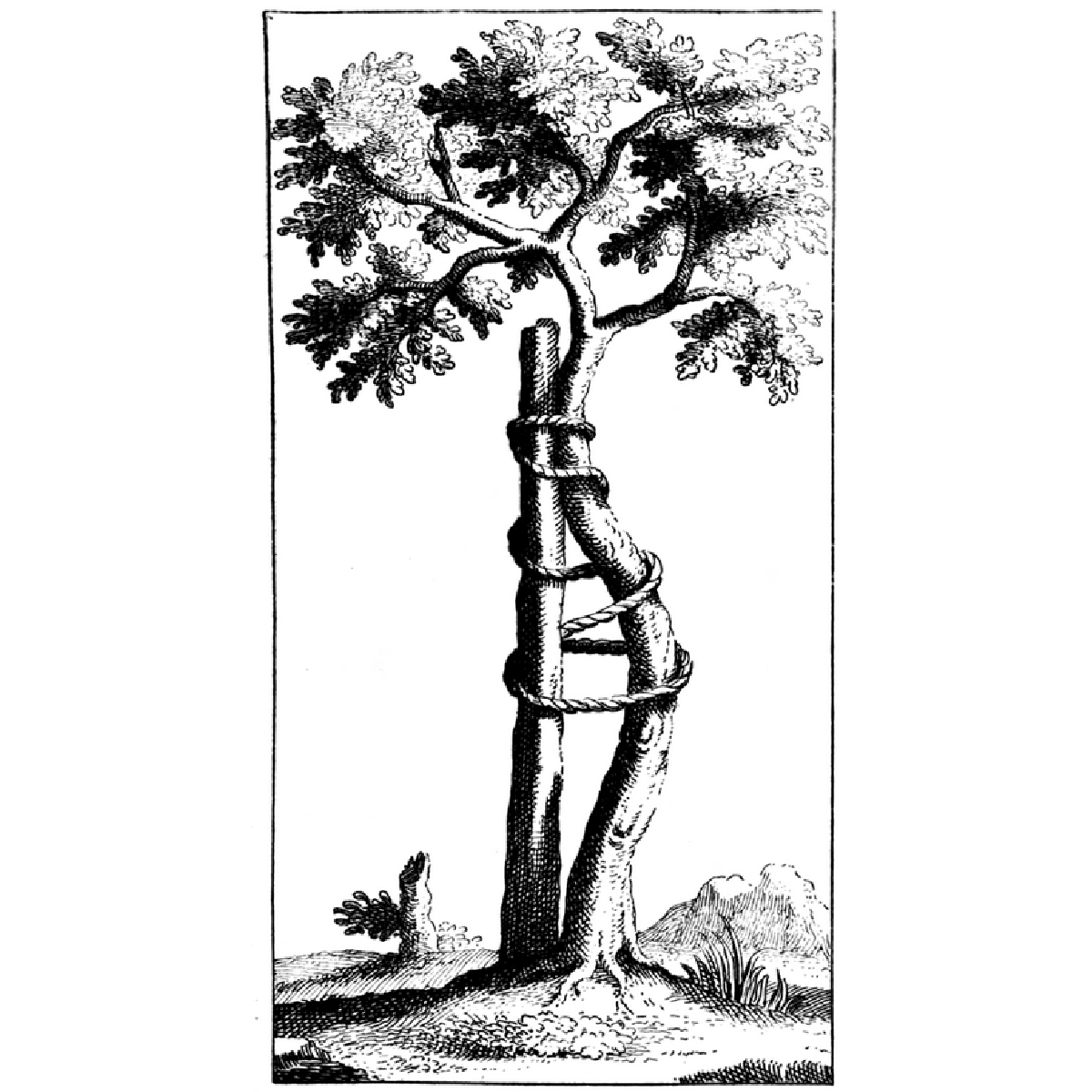

However, the tree has been subjected to power rather than being a source of it. Initially wild and free, trees were tamed, and this taming became a source of subjugation and oppression in general: Michael Marder put a stop to this antagonizing of trees. In his text In (Philosophical) Defense of Trees (2015), he wrote: “Deleuze and Guattari got ‘arborescence’ all wrong. The physical verticality of trees does not mean that they are vertical in the way they live or grow. Trees can branch out in quite unpredictable ways; they can accommodate the grafts of other species; they can give rise to shoots that would survive independently of them; they can change their sexes or become hermaphrodites for a part or for the rest of their lives; and the list goes on. To put it in Heideggerese, trees are ontically vertical and ontologically horizontal. Although they tower in measurable height over and above the grass, they are as egalitarian as the most humble of plants. In fact, given how some tree species share their root system, they can be thought of as overgrown grass. […] [T]rees, too, are rhizomes, proliferating between roots and shoots.” (3)